About the Author

Growing up in Washington, D.C., many of my friends were government officials’ kids. We all spoke the same language and , though we didn’t realize it at the time, shared the same culture. When I became a journalist, understanding the U.S. government’s side of the Laos “secret” war was not that hard for me, because the government’s culture and mine were pretty much the same. But understanding the Hmong side of the Laos war? That was different..

I first met Hmong people in 1980 in Ban Vinai refugee camp, in Laos’ neighbor Thailand. One night in camp I heard chanting and a jangling of cymbals nearby and went to investigate. A shaman dressed entirely in black, with a black veil over his eyes, was bouncing up and down on a bench as he chanted over his patient, who was lying on the ground on the ar side of a fire.

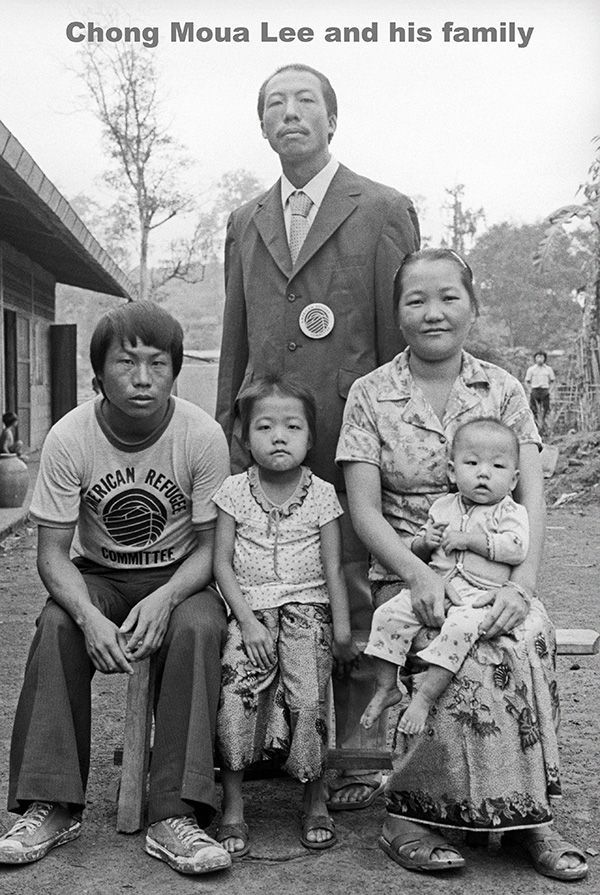

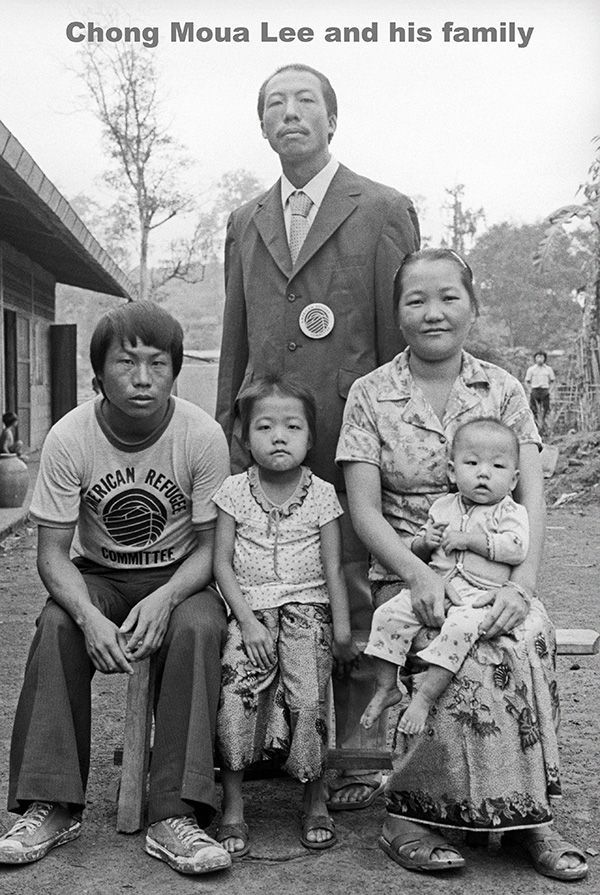

What’s he saying? I asked my interpreter, Chong Moua Lee, a former lieutenant in the Royal Lao Army, who is shown here with his family.

The answer came back, “He calling in B-52 jets to bomb the evil spirits.” That blew my mind, trying to summon American high-tech weaponry into the spirit world. Two entirely different cultures had collided, mashing together. My fascination with the Hmong and their epic journey began then and there.

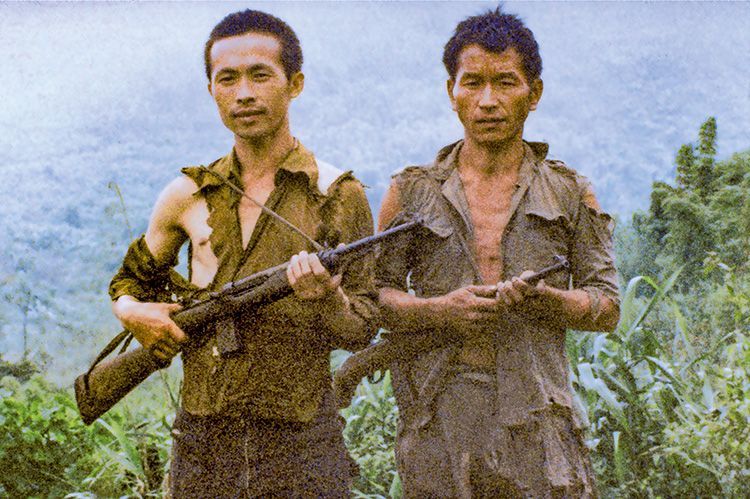

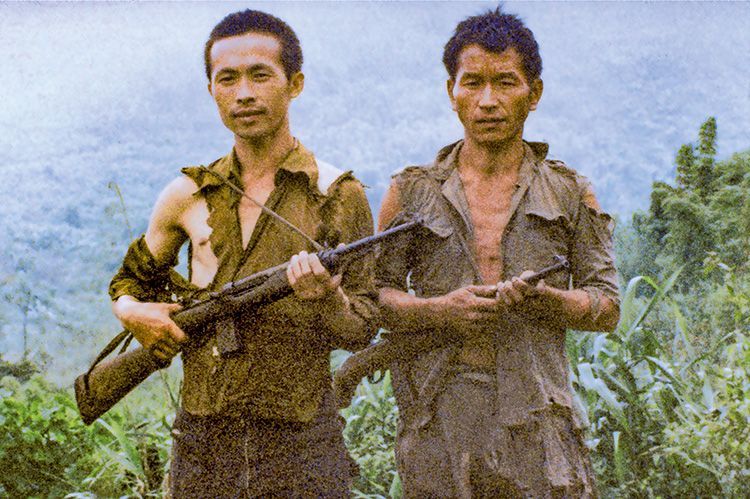

I had some luck when I was living in Thailand as a freelance journalist. For example, I gave a camera to a resistance team that was about to cross the Mekong River from Thailand to Laos. Back came an iconic photo showing a Hmong resistance in rough shape. That was the first image I collected that made it into this book.

I also got to know some genuinely impressive people, such as Lionel Rosenblatt, who ran the U.S. refugee program in Thailand, and one of his right-hand men, Mac Thompson. But I coudn’t figure out how to write about the Hmong story then. I didn’t speak the Hmong language, few Hmong in Ban Vinai spoke English, and the two Americans I met in Thailand who understood the story best – Pop Buell and Jerry Daniels – died before I could talk with them at length.

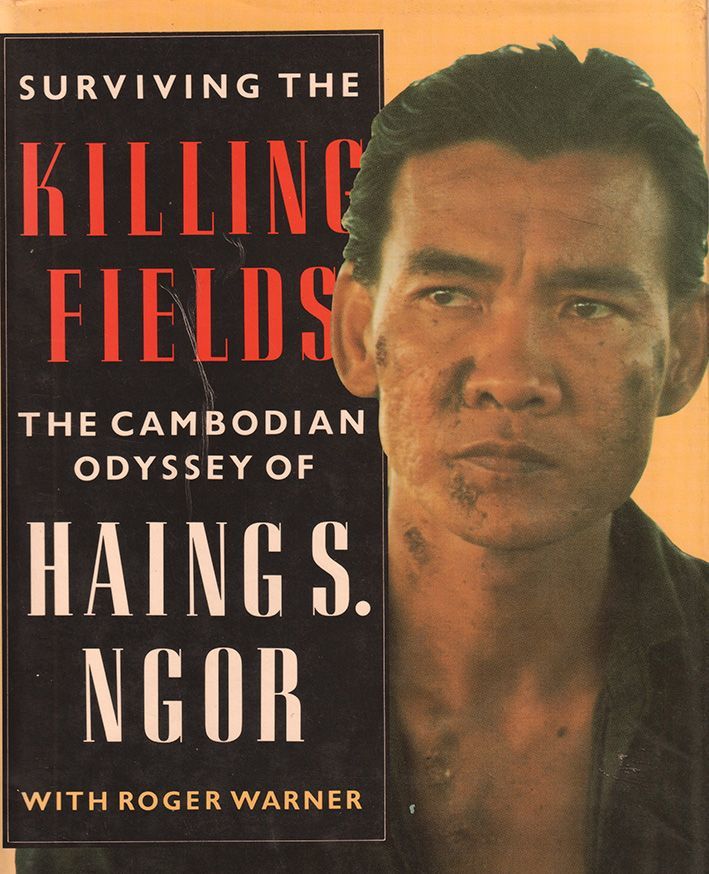

Eventually I went back to the States and wrote my first two nonfiction books: Invisible Hand, about dope smugglers and growers, and Surviving The Killing Fields: A Cambodian Odyssey, with Haing Ngor, a Cambodian doctor I’d met in a Thai refugee camp.

(After coming to America Ngor won an Academy Award for his role in the movie The Killing Fields).

But I always wanted to write about the Hmong. Visiting my parents in Washington, D.C., they told me to visit an ex-government employee who had just moved in down the street. This turned out to be Vint Lawrence, Gen. Vang Pao’s first CIA case officer in Long Cheng. Vint had become an artist and sophisticated political cartoonist. He read my Cambodia book, approved of it, and phoned his mentor, Bill Lair, in Texas, to introduce me. Lair, who was still in his PSTD phase, driving a truck long distances to help him clear his mind from the Laos war, agreed to meet me. He opened one door after another and a decades-long project began.

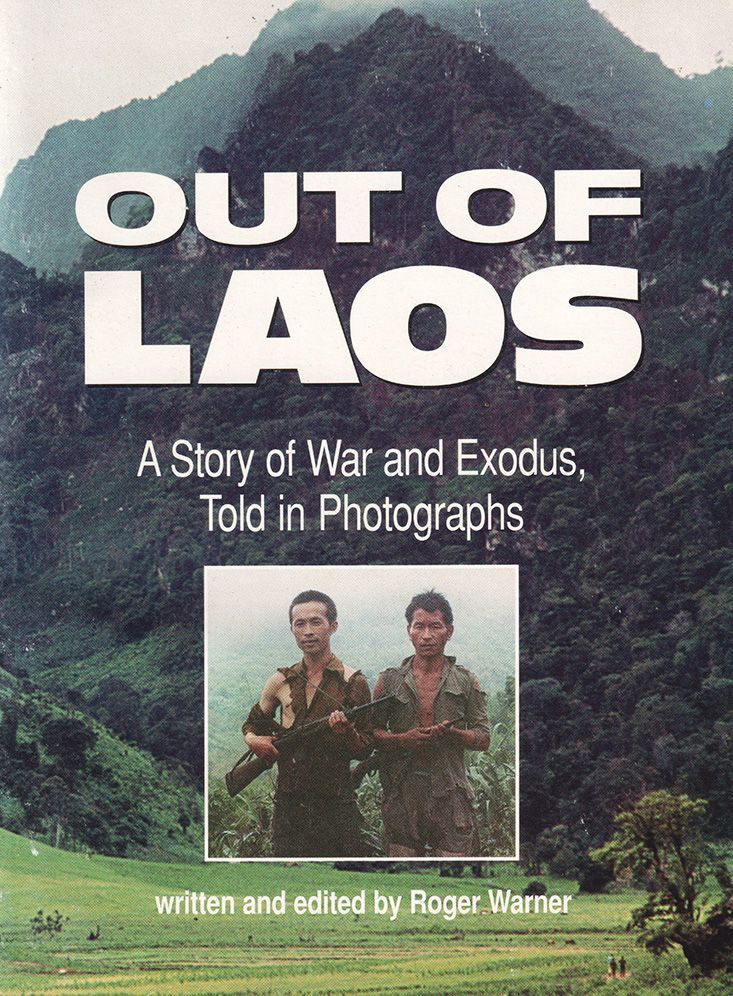

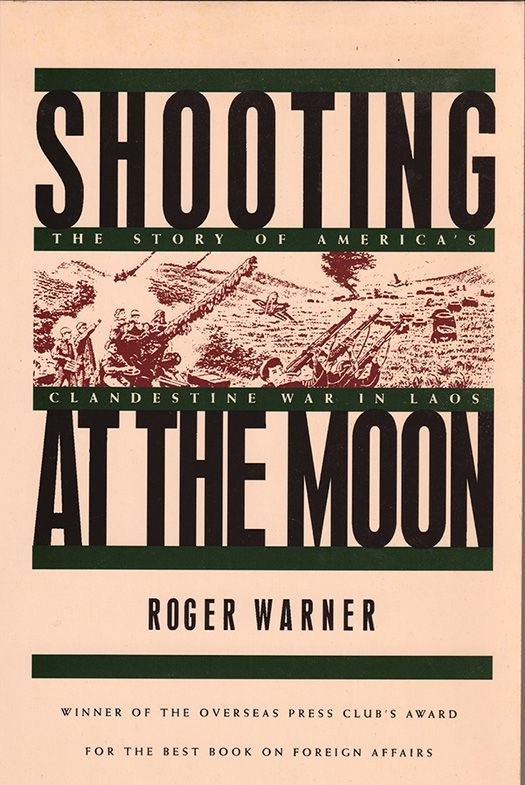

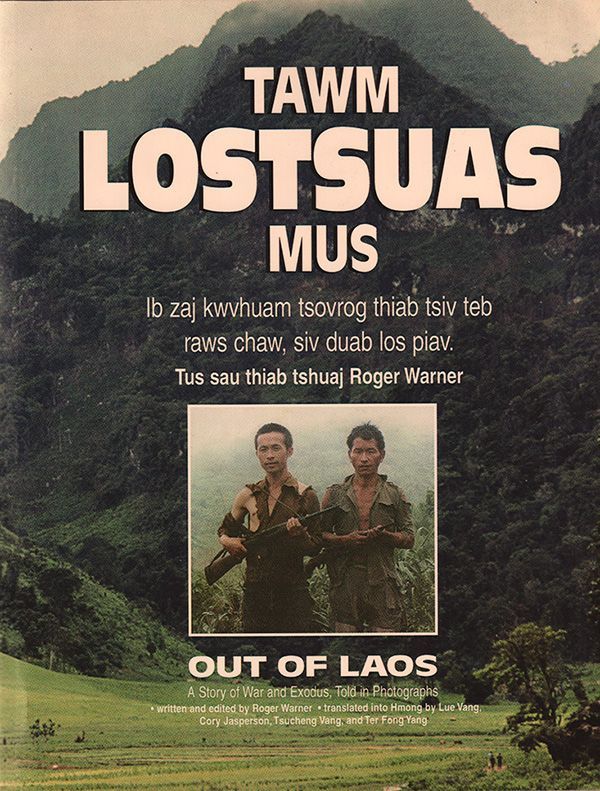

My first history of the Laos war came out in hardcover in 1995 under the title Back Fire, and in paperback under the title Shooting At The Moon. It won a prize and got good reviews but few Hmong were going to read nonfiction in English. So I came up with the idea of a visually-driven history of the Laos war for younger Hmong-Americans. The first edition of Out of Laos, published in 1998 both in English and in Hmong, was funded by a tiny grant, and printed in black-and-white on a glorified Xerox copier. It was about a third of the length of the version you see now.

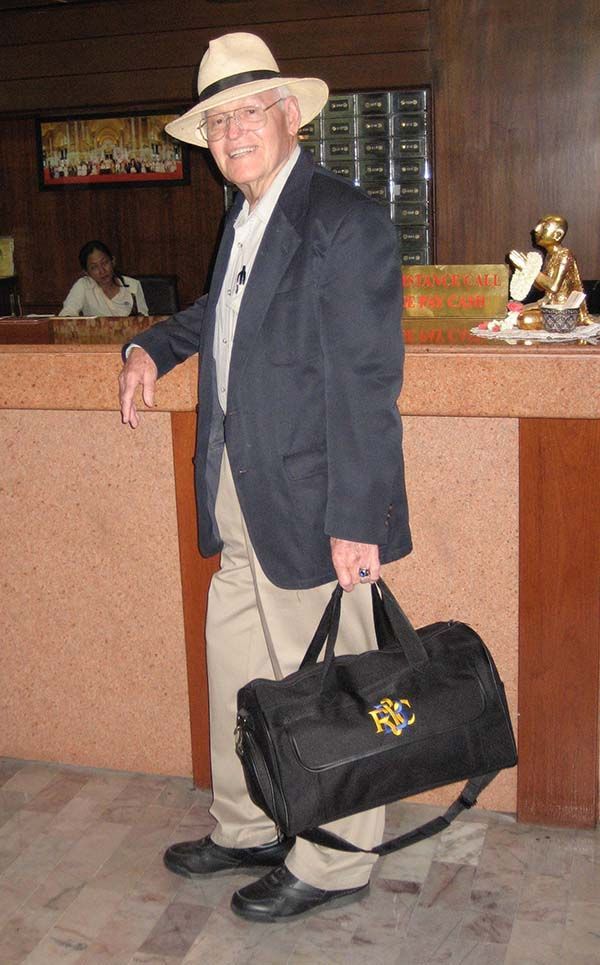

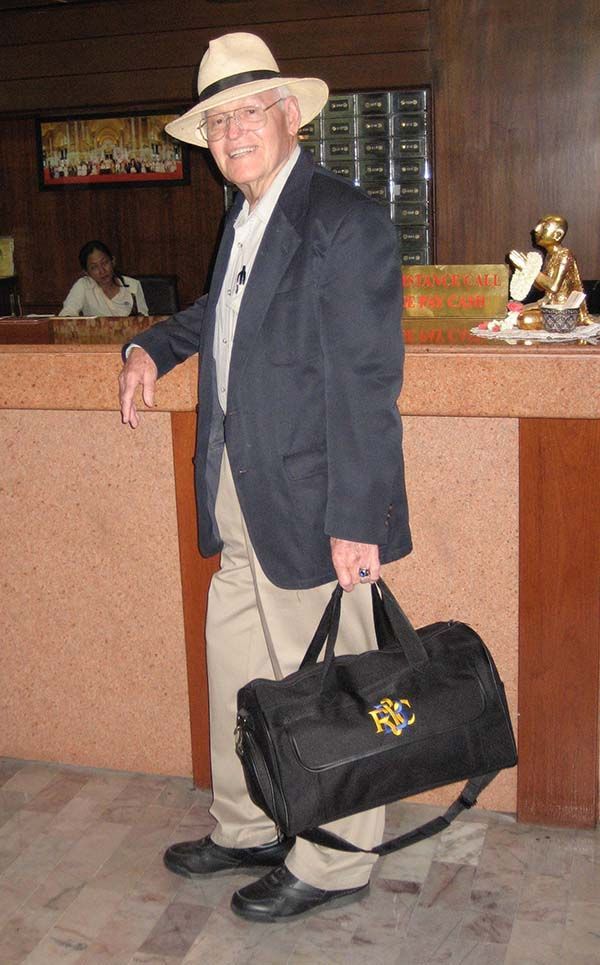

After that, I kept following the Hmong story, traveling around the U.S. and to Laos and Thailand with Bill Lair, and around the U.S. with General Vang Pao. I got to know the general a bit, to the extent that any non-Hmong speakers could know a man as complex as that. Often with Bill Lair at my side, but sometimes alone, I attended Hmong New Years and conferences and festivals with the general and talked with him many times. When he was arrested in 2007, I did volunteer work for his lawyers.

During the 2010s, after Gen. Vang Pao’s funeral and then Bill Lair’s funeral, my understanding of the long journey of the Hmong began coming together a little at a time, like the pieces of an enormous jigsaw puzzle. The Covid lockdown finally gave me the chance to begin expanding Out of Laos to its current length (608 pages!) and print it in color. The layout format I used, with most of the images running across two facing pages, and connecting them with narrative text, was influenced by documentary films, by the extended photo essays in the old LIFE magazine of the 1940s and 1950s, and by graphic novels.

My thanks go to all those who helped me along the way. Hundreds of people made a difference, but above all I want to thank Lar Yang and David Lee of Hmongstory Legacy in Fresno. Without their advice, and without their extraordinary photograph collection, which included the priceless images shot by the late, great Erica Hagen, I couldn’t have even attempted to take on my deepest theme – which, believe it or not, is not the Hmong or even the perils of American intervention overseas.

My deepest theme is the challenge of navigating between radically different cultures. Anytime, anywhere.

That is to say, Out of Laos is of course about the Hmong, but its lessons, and its parallels resonate with many cross-cultural situations. We live in an interconnected world. Cross-cultural clashes pop up all around us, all the time. No two are the same, but they related patterns, like the images generated one after the next by a kaleidoscope. Because of this, I feel that Out of Laos is, ultimately, an even larger story than the remarkable and dramatic story of America’s Hmong people.

About the Author

Growing up in Washington, D.C., many of my friends were government officials’ kids. We all spoke the same language and , though we didn’t realize it at the time, shared the same culture. When I became a journalist, understanding the U.S. government’s side of the Laos “secret” war was not that hard for me, because the government’s culture and mine were pretty much the same. But understanding the Hmong side of the Laos war? That was different..

I first met Hmong people in 1980 in Ban Vinai refugee camp, in Laos’ neighbor Thailand. One night in camp I heard chanting and a jangling of cymbals nearby and went to investigate. A shaman dressed entirely in black, with a black veil over his eyes, was bouncing up and down on a bench as he chanted over his patient, who was lying on the ground on the ar side of a fire.

What’s he saying? I asked my interpreter, Chong Moua Lee, a former lieutenant in the Royal Lao Army, who is shown here with his family.

The answer came back, “He calling in B-52 jets to bomb the evil spirits.” That blew my mind, trying to summon American high-tech weaponry into the spirit world. Two entirely different cultures had collided, mashing together. My fascination with the Hmong and their epic journey began then and there.

I had some luck when I was living in Thailand as a freelance journalist. For example, I gave a camera to a resistance team that was about to cross the Mekong River from Thailand to Laos. Back came an iconic photo showing a Hmong resistance in rough shape. That was the first image I collected that made it into this book.

I also got to know some genuinely impressive people, such as Lionel Rosenblatt, who ran the U.S. refugee program in Thailand, and one of his right-hand men, Mac Thompson. But I coudn’t figure out how to write about the Hmong story then. I didn’t speak the Hmong language, few Hmong in Ban Vinai spoke English, and the two Americans I met in Thailand who understood the story best – Pop Buell and Jerry Daniels – died before I could talk with them at length.

Eventually I went back to the States and wrote my first two nonfiction books: Invisible Hand, about dope smugglers and growers, and Surviving The Killing Fields: A Cambodian Odyssey, with Haing Ngor, a Cambodian doctor I’d met in a Thai refugee camp.

(After coming to America Ngor won an Academy Award for his role in the movie The Killing Fields).

But I always wanted to write about the Hmong. Visiting my parents in Washington, D.C., they told me to visit an ex-government employee who had just moved in down the street. This turned out to be Vint Lawrence, Gen. Vang Pao’s first CIA case officer in Long Cheng. Vint had become an artist and sophisticated political cartoonist. He read my Cambodia book, approved of it, and phoned his mentor, Bill Lair, in Texas, to introduce me. Lair, who was still in his PSTD phase, driving a truck long distances to help him clear his mind from the Laos war, agreed to meet me. He opened one door after another and a decades-long project began.

My first history of the Laos war came out in hardcover in 1995 under the title Back Fire, and in paperback under the title Shooting At The Moon. It won a prize and got good reviews but few Hmong were going to read nonfiction in English. So I came up with the idea of a visually-driven history of the Laos war for younger Hmong-Americans. The first edition of Out of Laos, published in 1998 both in English and in Hmong, was funded by a tiny grant, and printed in black-and-white on a glorified Xerox copier. It was about a third of the length of the version you see now.

After that, I kept following the Hmong story, traveling around the U.S. and to Laos and Thailand with Bill Lair, and around the U.S. with General Vang Pao. I got to know the general a bit, to the extent that any non-Hmong speakers could know a man as complex as that. Often with Bill Lair at my side, but sometimes alone, I attended Hmong New Years and conferences and festivals with the general and talked with him many times. When he was arrested in 2007, I did volunteer work for his lawyers.

During the 2010s, after Gen. Vang Pao’s funeral and then Bill Lair’s funeral, my understanding of the long journey of the Hmong began coming together a little at a time, like the pieces of an enormous jigsaw puzzle. The Covid lockdown finally gave me the chance to begin expanding Out of Laos to its current length (608 pages!) and print it in color. The layout format I used, with most of the images running across two facing pages, and connecting them with narrative text, was influenced by documentary films, by the extended photo essays in the old LIFE magazine of the 1940s and 1950s, and by graphic novels.

My thanks go to all those who helped me along the way. Hundreds of people made a difference, but above all I want to thank Lar Yang and David Lee of Hmongstory Legacy in Fresno. Without their advice, and without their extraordinary photograph collection, which included the priceless images shot by the late, great Erica Hagen, I couldn’t have even attempted to take on my deepest theme – which, believe it or not, is not the Hmong or even the perils of American intervention overseas.

My deepest theme is the challenge of navigating between radically different cultures. Anytime, anywhere.

That is to say, Out of Laos is of course about the Hmong, but its lessons, and its parallels resonate with many cross-cultural situations. We live in an interconnected world. Cross-cultural clashes pop up all around us, all the time. No two are the same, but they related patterns, like the images generated one after the next by a kaleidoscope. Because of this, I feel that Out of Laos is, ultimately, an even larger story than the remarkable and dramatic story of America’s Hmong people.